OR: How digital media broke civic engagement.

Civic engagement and political participation are a common dependent variable in studies that explore the political impact of digital media and the internet. They refer to the ways in which, or degrees to which, people engage and participate in civic issues and politics. But I’ve found the use of the terms to be confusing, simultaneously diffuse and overlapping. So I did a quick review of the literature to figure out what was what. Here’s what I found.

State of the art

Civic engagement and political participation are both very well established concepts in the fields of political science and communication studies. They are both also very broadly construed, to include a whole host of activities.

According to the 2016 International Encyclopedia of Political Communication,

…the list of specimens of political participation is virtually endless and includes activities such as voting, demonstrating, donating money, contacting a public official and boycotting, but it also includes guerilla gardening, volunteering, attending flash mobs, buying fair-trade products, and even suicide protests” (van Deth, 2016: 1158-1159).

The Encyclopedia’s entry on civic engagement advances a similarly broad conceptualization, noting multiple accepted inflections for both “civic” (which can imply “all manner of behavior which can be seen as socially considerate or beneficial,” including “not littering.”) and “engagement” (which is often used as a synonym for both “involvement” and “participation”). On the basis of this diverse usage. The entry’s author argues for understanding civic engagement as a general disposition among citizens which facilitates participation, defined in contradistinction to civic disengagement, or political apathy. (Dahlgren, 2016: 119-124)

The breadth described above is also clearly evident in the literature, with studies including everything from buying fair trade brands (de Zuniga et al, 2014), to blogging and protest on gaming and entertainment sites (Jenkins et al, 2006, cited in Bennet, 2008: 2), to participation in hackathons (Schrock, 2012). Several authors have merged and innovated on the terminology, spawning conceptual objects such as “democratic engagement” (Hampton, 2011) or “civic political engagement” (Koc-Michalska et al, 2014). Others have proposed or implied a continuum of actions, in which civic engagement represents passive activities or latent participation, and political participation represents explicit and intentional acts (Ekman & Amnå, 2012: 292; Dahlgren, 2016: 120). Other scholars deliberately introduce new concepts in response to the conceptual poverty of those provided. Thus Ethan Zuckerman (2014) has proposed participatory civics “to refer to forms of civic engagement that use digital media as a core component” (156), and Dalton (2008) distinguishes between elite-directed and self-directed forms of participation. But such deliberate and generative efforts are in the minority, and the bulk of relevant scholarship still adheres to these two terms,and the dramatic diversity they convey.

This is a problem. Precision matters. As Ekman & Amnå note in their study of the rhetoric, “If civic engagement is used by scholars to mean completely different things, it is basically a useless concept—it confuses more than it illuminates” (2012: 284). Before even thinking about how to address this problem, we need to understand how it emerged in the first place.

So how did we get here?

Civic engagement has traditionally been a broad and amorphous concept, due in part to the multiple valences attached to each of the two words that compose it, as noted in the encyclopedia entry above. Just as much to blame is Putnam, who popularized the term in the early 90’s and emphasised the importance of social capital to citizen engagement, thus included everything from reading newspapers to bowling, without ever providing a definition (Ekman & Amnå, 2012: 283-284). Other scholars took this inclusive ambiguity and ran with it, defining civic engagement as “all the ways in which individuals participate in public life“ (Bala, 2014: 766) or “actions citizens take in order to pursue common concerns (Zukin et al., 2006), cited in Skoric et al (2016:1822)). The concept has grown steadily, and all the more so with the introduction of things like facebook and government websites (Koc-Michalska, 2014; Kaun et al, 2016).

The concept of political participation, on the other hand, began with a much narrower definition focused almost exclusively on electoral participation, (hich Ekman & Amnå (2012) note was closely linked to electoral centrism across the political sciences (285)). But an emphasis on actions that attempt “to influence others […] and their decisions that concern societal issues“ allowed for the concept to swell over time and eventually include a variety of activities, including issue-focused community activities, boycotts, and participating in labour strikes (Ekman & Amnå, 2012: 285-286).

Similar to civic engagement, political participation has also expanded to include new types of activities that are enabled by digital media, whether that involves e-campaigning, political groups on Facebook or online petitions, which Van Deth (2016) describes as an “expansion of the concept of political participation” since the second world war (1160-1161). Several scholars note that this cultural trend is not a singular driver of the phenomenon however. The tendency for political scientific concepts to swell and incorporate increasingly diverse empirical phenomena has a rich tradition, often referred to as “conceptual stretching.”

From stretching to tech-ing

Conceptual stretching was first introduced in Sartori’s (1970) wonderfully grumpy critique of political science, as more countries were established, and bought into the purview of comparative studies (“There were about 80 States in 1946; it is no wild guess that we may shortly arrive at 150” (1034)):

That is to say, the larger the world, the more we have resorted to conceptual stretching, or conceptual straining, i.e., to vague, amorphous conceptualizations (1034).

As a result we do not obtain a more general concept, but its counterfeit, a mere generality (where the pejorative “mere” is meant to restore the distinction between correct and incorrect ways of subsuming a term under a broader genus.) (1041).

The idea of conceptual stretching has since been applied to a number of concepts and fields, including the two concepts discussed here (Adler and Goggin, 2005; Ekman & Amnå, 2012).

Several scholars have also noted social and cultural trends at play. Van Deth (2016) describes a “growing salience of government and politics for everyday life, the blurring of the distinction between private and public spheres” (1159). Zuckerman notes that cultural shifts are also closely entangled with the ways in which we use media, and argues that “a broadening definition of civics” and “an additional shift in the definition of citizenship” are necessary to understand how new media are impacting “civics” (2014: 155). Bimber (2002) goes further to implicate technological developments in these trends, noting that digital media have the tendency not only to morph the ways in which citizens engage and participate, but to move civic action away from traditional institutions of governance (Bimber, 2012: 115).

Wrapping up

So there’s a lot going on, but it seems safe to say that at least three parallel tendencies underlie the conceptual diffusion and co-mingling of civic engagement and political participation.

Firstly, there is an academic “path of least resistance” implicated by conceptual stretching. It’s easier to call something by a known name, especially when it’s a dependent variable, than to disentangle empirical soup and reify concepts. Secondly, there’s the cultural phenomenon of politics and civics encroachment into daily life and an increasingly popular understanding that everything is political (I hope that butter on your bread doesn’t have palm oil in it). Thirdly, digital media have introduced new models of engagement and participation, digitized others, and generally forced a reconception about how politics and political communication work. How those trends fit together and mutually reinforce each other is a million dollar question.

In terms of what the literature says, I think there are at least a handful of distinctions that can be identified and strengthened through their usage. These are of course up for debate.

- Citizen engagement is about the positions and perspectives held by individuals, political participation is about the actions taken by individuals.

- Citizen engagement latent and passive, implying that is sequentially or causally related to political participation, which is dynamic and active.

- Citizen engagement is a broad paradigmatic collection of activities, political participation is a gradient continuum of activities

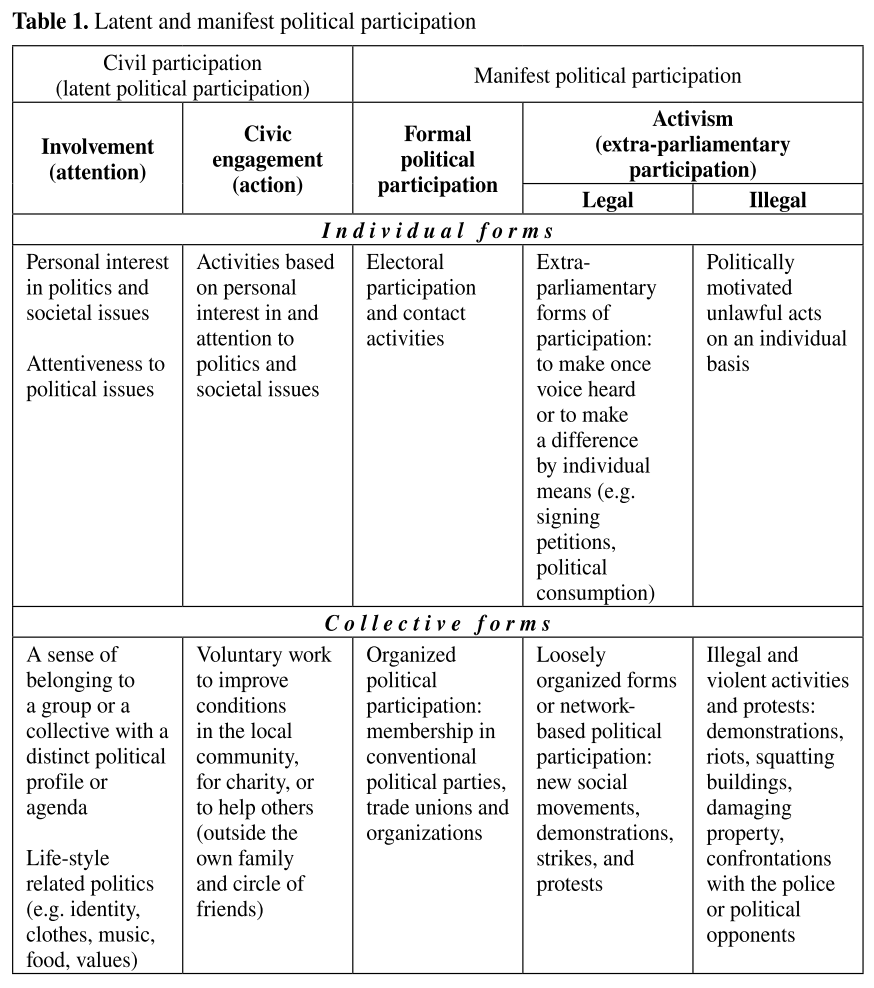

In terms of what to do about it all, I think the notion of a continuum is conceptually useful. Ekman & Amnå (2012) propose the one below, which implies a sequential progression from civic engagement to political participation. It’s not perfect, but seems a good start towards greater conceptual clarity.

With this general approach in mind, I would also expect concept proliferation to be useful, producing new concepts on the basis of structural processes rather than platforms (cf: Bimber, 2012: 121). In pursuing this, it’s also important to keep in mind that both these concepts are inherently normative (Bennet, 2008: 4), and it might not be wise, especially in today’s age of alternative facts, populism and distrust of elites,, to assume without question that increased engagement and participation are in themselves good things.

Which brings us back to the original question, how are things like civic engagement and political participation affected by the introduction of digital media and related innovations? Well, there’s no easy answer of course, and some argue that digital media only make traditional modes of participation “more convenient or more efficient” (Van Deth, 2016: 1162). But the literature is generally positive, with a whole slew of optimism and cyber utopianism still evident (Vigoda, 2002, Charalabidis et al, 2012; Gurevitch et al, 2009). This has been borne out by actual studies to some degree. In addition to enabling novel forms of engagement and participation online (Evans-Cowley & Hollander, 2010), several studies have showed that specific uses of digital media promote offline civic engagement and political participation (McLeod & Lee, 2012: 15; Feezell et al, 2016; Tedesco, 2007; Shamaileh, 2016; de Zúñiga et al, 2010; Mossberger & Tolbert, 2010).

But there’s a whole host of messy relationships at play here, so consensus and clear conclusions will be a long time coming, methinks. This all the more so in contemporary politics, where it’s tempting to see new modes of political mobilization and actualizing citizenship in the American left’s response to the early days of the Trump administration. We shall see if the concepts can be disentangled and clarified before they’re completely broken again by novel politics.

REFERENCES

Adler, R. P. (2005). What Do We Mean By “Civic Engagement”? Journal of Transformative Education, 3(3), 236–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344605276792

Bala, M. (2014). Civic Engagement in the Age of Online Social Networks. Contemporary Readings in Law and Social Justice, 6(1), 767–774.

Bennett, W. L. (2008). Changing Citizenship in the Digital Age. In W. L. Bennett (Ed.), Civic Life Online: Learning How DigitalMedia Can Engage Youth (pp. 1–24). Cambridge, Mas: MIT PressCac. https://doi.org/10.1162/dmal.9780262524827.001

Bimber, B. (2012). Digital Media and Citizenship. In H. A. Semetko & M. Scammell (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Communication (pp. 115–127). London: SAGE Publications Lt. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446201015.n10

Bimber, B. (1999). The Internet and Citizen Communication With Government: Does the Medium Matter? Political Communication, 16(4), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/105846099198569

Carpini, M. X. D., Cook, F. L., & Jacobs, L. R. (2004). PUBLIC DELIBERATION, DISCURSIVE PARTICIPATION, AND CITIZEN ENGAGEMENT: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Annual Review of Political Science, 7(1), 315–344. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.7.121003.091630

Charalabidis, Y., & Koussouris, S. (2012). Collaboration for Open Innovation Processes in Public Administrations. (Y. Charalabidis & S. Koussouris, Eds.), Empowering Open and Collaborative Governance: Technologies and Methods for Online Citizen Engagement in Public Policy Making. Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-27219-6

Dahlgren, P. (2016), Civic Engagement. In G. Maxxoleni, K. G. Barnhurst, K. Ikeda, R. C. M. Maia, & H. Wessler (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

de Zuniga, H. G., Copeland, L., & Bimber, B. (2014). Political consumerism: Civic engagement and the social media connection. New Media & Society, 16(3), 488–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813487960

de Zúñiga, H. G., Veenstra, A., Vraga, E., & Shah, D. (2010). Digital Democracy: Reimagining Pathways to Political Participation. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 7(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331680903316742

Ekman, J., & Amnå, E. (2012). Political participation and civic engagement: Towards a new typology. Human Affairs, 22, 283–300. https://doi.org/10.2478/s13374-012-0024-1

Evans-Cowley, J., & Hollander, J. (2010). The New Generation of Public Participation: Internet-based Participation Tools. Planning Practice and Research, 25(3), 397–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2010.503432

Feezell, J. T., Conroy, M., & Guerrero, M. (2016). Internet Use and Political Participation: Engaging Citizenship Norms Through Online Activities. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 1681(May), 19331681.2016.1166994. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2016.1166994

Gurevitch, M., Coleman, S., & Blumler, J. G. (2009). Political Communication –Old and New Media Relationships. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 625(1), 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716209339345

Haller, M., Li, M.-H., & Mossberger, K. (2011). Does E-Government Use Contribute to Civic Engagement with Government and Community ? In APSA 2011 Annual Meeting Paper (pp. 1–34). Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1901903

Hampton, K. N. (2011). Comparing Bonding and Bridging Ties for Democratic Engagement. Information, Communication & Society, 14(4), 510–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.562219

Kaun, A., Kyriakidou, M., & Uldam, J. (2016). Political Agency at the Digital Crossroads? Media and Communication, 4(4), 1. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i4.690

Koc-Michalska, K., Lilleker, D., & Vedel, T. (2014). Civic political engagement and public spheres in the new digital era. New Media & Society, 18(9), 1807–1816. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815616218

McLeod, J. M., & Lee, N.-J. (2012). Public Discussion and Civic Engagement: A Socialization Perspective. In H. A. Semetko & M. Scammell (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Political Communication (pp. 197–209). SAGE Oublications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446201015

Mossberger, K., & Tolbert, C. J. (2010). Digital Democracy: How Politics Online is Changing Electoral Participation. The Oxford Handbook of American Elections and Political Behavior, (November), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199235476.003.0012

Sartori, G. (1970). Concept Misformation in Comparative Politics. The American Political Science Review, 64(4), 1033–1053.

Schrock, A. R. (2012). Civic hacking as data activism and advocacy: A history from publicity to open government data. New Media & Society, 18(4), 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816629469

Shamaileh, A. (2016). Am I equal ? Internet access and perceptions of female political leadership ability in the Arab world, 1681(May). https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2016.1163518

Skoric, M. M., Zhu, Q., Goh, D., & Pang, N. (2016). Social media and citizen engagement: A meta-analytic review. New Media & Society, 18(9), 1817–1839. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815616221

Tedesco, J. C. (2007). Examining Internet Interactivity Effects on Young Adult Political Information Efficacy. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(2005), 1183–1194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764207300041

Van Deth, J. (2016). Political Participation. In G. Maxxoleni, K. G. Barnhurst, K. Ikeda, R. C. M. Maia, & H. Wessler (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Vigoda, E. (2002). From Responsiveness to Collaboration: Governance, Citizens, and the Next Generation of Public Administration. Public Administration Review, 62(5), 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00235

Zuckerman, E. (2014). New Media, New Civics? Policy and Internet, 6(2), 151–168.