Stefaan G. Verhulst recently offered some suggestions on how to “build a civic tech field that can last and stand the test of time.” Stefaan is a smart guy, connected, well informed, and his suggestions make smart sense of a messy landscape. But they also accept a fundamental premise which tends to go unchecked in international discussions about civic tech.

His introduction:

…we are yet to witness a true tech-enabled transformation of how government works and how citizens engage with institutions and with each other to solve societal problems. In many ways, civic tech still operates under the radar screen and often lacks broad acceptance. So how do we accelerate and expand the civic tech sector? How can we build a civic tech field that can last and stand the test of time?

I think this represents a popular perspective, but would argue that there’s a hidden question begged. The need for a strong sector or community does not follow directly from widely recognized promise and lack of significant impact. I’m all for the exciting way in which civic tech can strengthen governance, civic engagement and quality of life, but would like to suggest that we might not need a civic tech sector for that at all, at least not in the sense of a scope of work defined by common interests. It might even be getting in the way.

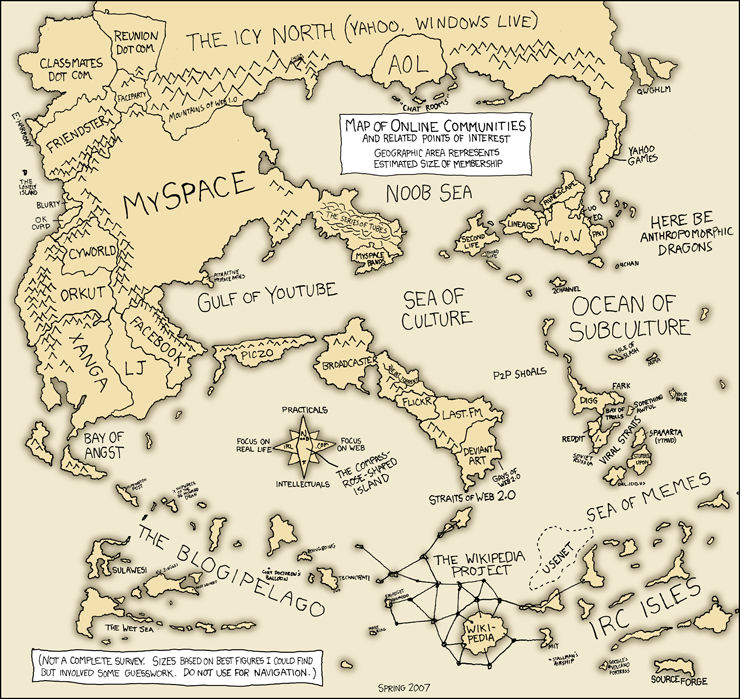

To start with, civic tech does a lot of different things. It’s commonly understood to span elections, health care, budgets, public service delivery and more (even airbnb by some accounts). This has led to more than a few interesting debates about what to name it. But this naming fascination might just be our bike shed.

After all, what does the use of drone-facilitated land concession monitoring by indigenous rainforest communities have to do with apps to fight parking tickets or innovation hubs launched in North American “smart cities”? Something called technology, by which we seem to mean anything that involves the internet, coding, or which is in some way able to do fancy tricks.

Technology does not a field make.

Technology can facilitate novel and innovative solutions to deeply contextual problems, but rarely produces cookie cutter or scaleable solutions. Civic tech recognizes this in the abstract, and our community’s cannon is rife with with recommendations to build from context. We all know that context is king. But somehow we have conceptualized technology in the abstract as the touchstone for defining our community. This has two negative consequences.

Firstly, accepting such a vague qualifier for the civic tech community encourages us to believe that knowledge transfers can do more than they likely can. We all want to see lessons and expertise that have been gained through civic tech programming applied to new programming, so that the wheel doesn’t get reinvented. We hate to see duplication and repeated mistakes. But as we know from international development, digital security and other fields, parachuting experts really doesn’t lead to organizational or systemic change.

Sometimes you have to reinvent the wheel because wheels work differently in different contexts, and talking about civic tech as a catholic community obscures this. It’s not that our failure to name ourselves keeps us from learning. It’s the idea that we share enough to learn collectively, which keeps us teaching the obvious lessons, over and over. At the end of the day, it’s worth asking if there ever was a non-bespoke civic technology that made a bit of difference.

The idea that anything using technology for civic ends ought to be comparable and included within the same schools of expertise or community networks is just plain silly. Or as Waller and Weerakkody quipped in their recent white paper on digital government:

Before the Internet no one would have set out to transform government and public administration by redesigning forms and guidance pamphlets.

Secondly, the idea of a universal civic tech community sucks a lot of resources out of the room. We, as a “community”, spend a lot of time and energy mapping out what and how we are a community, and fund a lot of mechanisms and positions to bolster up an expertise and and set of interactions which don’t do a lot of good. That time and money could be better spent elsewhere, on efforts to strengthen the strategic nuts and bolts of technology in specific contexts, driven by context.

And at the end of the day, we don’t need a global all encompassing civic tech community to accomplish that community’s goals. Stefaan’s post offers a handful of recommendations for designing a civic tech community that can last. Each of these can be very usefully applied to smaller communities (say budget monitoring communities, or technology driven land rights initiatives in sub saharan africa), and indeed already are. But when it comes to identifying the signal in the noise of civic tech, I think that’s an endeavor doomed not only to fail, but to distract us from where change actually happens.

The noise of the civictech community’s obsession with self, comes from the fact that it’s not a community in any meaningful sense, and the fact that there are perverse incentives for that community to be institutionalized and to embed itself in the non-profit landscape. It’s absolutely right to assert that “we need intermediaries that can move from delivering “facts” to exposing and amplifying patterns; and leverage those patterns to move from information to intelligence,” but I think that implies work at the level of applied technology, not for the presumed sector as a whole.

Language matters

This is the distinction that was largely missed when Dan O’Neil suggested that the civic tech movement “be shelved”.

It’s not that tech can’t do good, but that tech needs deeply contextualized strategy and political economy to do that good, and vague ideas about the civic tech community obscure that reality.

So let’s stop talking about civic tech community and start talking about civic tech tools and activities with a specificity that matters. What does it mean?

- It does not mean we stop sharing insights and experiences. We should continue to do that and do it better, in a targeted way across contexts and initiatives that are similar enough to gain from it.

- We should stop assuming platforms and networking mechanisms which span the entirety of #civictech will do anything useful at all, aside from funding the positions of more experts. It’s time to stop wasting time and funding on Democracy Machines, universal toolboxes, and that one perfect web portal to rule them all, through which all knowledge of civic tech will pass.

- We should stop talking about a civic tech community, and start talking about the networks, ecosystems and tools of civic tech. This might allow us to continue improving work, without falling into the build it and they will come trap.

These might seem like subtle distinctions, but they’re distinctions with a difference. They might be a first step towards organizing ourselves systemically, instead of trying to capture all things to get all the grants.

That’s all. I’ll stop now.